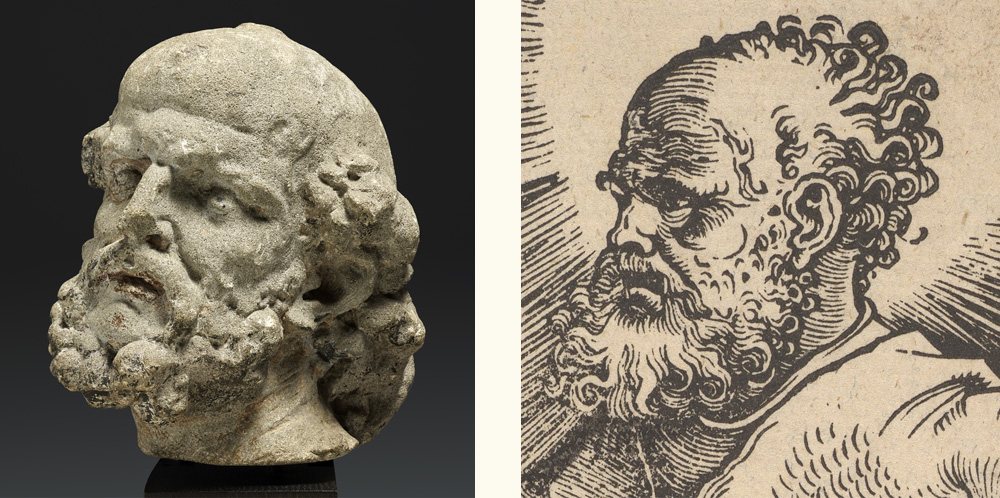

A Striking Head of Saint Paul

This impressive head depicts a bearded man caught in a moment of powerful dramatic expression. The head swerve, the gaze turned suddenly upwards, the contraction of the forehead, his corrugated eyebrows and the small mouth with fleshy lips, describe effectively the intense emotion of the character.

The sculptor lingered in the detailed rendering of the curly hair and beard, in the different kind of wrinkles that mature skin can show when exposed to sunlight and in the peculiar shape of the cranium: for sure these are the results of a careful and extended physiognomic observation.

The traces of a naturalistic polychromy – well identifiable in many areas of the sculpture like skin tone, pupils, red lips, dark hair and beard – represent a rare and precious element for a sandstone Renaissance sculpture.

Both the kind of sandstone and the carving of the present head resemble some of the few surviving stone sculptures achieved between the late 15th and the early 16th century in the area of Strasbourg, a region where along the centuries French art intertwines with German art. Particularly, the realistic description of the furrowed brow, the high cheekbones and the way fleshy eyebrows surround the eyes, as well as the fine and light carving of the surface describing wrinkles and skin, can be related to the work by Niclaus Gerhaert (Nikolaus von Leyden, Nicolas de Leyde; c. 1420 – after 1472).

Niclaus Gerhaert was doubtless among the most influential northern European sculptors of the 15th century. From 1462 to 1467, Gerhaert worked in Strasbourg where he achieved the Great door of the Strasbourg Chancellery: the Head of a Prophet with Turban provides notable points of comparison with the present head.

His talent in rendering naturalistic details, particularly in his faces -deeply rooted in the art of his native land, Holland- is influenced by major sculptors like Claus Sluter, and connected to the art of Veit Stoss and Tilman Riemenschneider.

However, the Gothic graphical lines typical of the late 15th century sculpture (such as that by Gerhaert, or other sculptors of the same area like Lux Kotter or Veit Wagner, or Nicolas de Haguenau, particularly in the Issenheim Altarpiece, now in Colmar, Unterlinden Museum) are here overcome, towards a more realistic and natural way of depicting hair, flesh and the face in general, allowing to date the present sculpture to the first decades of the 16th century.

As for the subject represented by this powerful sculpture, it is probably Saint Paul: in fact, the iconography of the Apostle, as proven both by art and literature, recalls that of Philosophers, emphasising his intellectual qualities (baldness, a broad forehead and a furrowed brow); also, a beard was traditionally associated the Jews, as well as a protruding nose.

The dramatic energy of this face is provided by intense shades created by a deep carving; furthermore, the realistic depiction of ‘old age’ in Gothic art commonly identified Saints as ascetic and spiritually ‘Holy Men’. Sometimes this devotional realism can give almost the effect of a portrait.

Realism is after all a typical feature of Franco-Flemish visual culture and it appears also in wooden sculpture, paintings and engravings, such as those by Martin Schongauer, Albrecht Dürer and Hans Baldung Grien.

HEAD OF SAINT PAUL

Limestone with traces of polychromy

France (Strasbourg?)

First half 16th century

H cm. 24

Provenance: Boccador collection (Paris)

Related Litterature: Niclaus Gerhaert: der Bildhauer des Späten Mittelalters, exhibition catalogue (Liebieghaus Skulpturensammlung, Frankfurt am Main, 27 October 2011- 4 March 2012; Musée de l’Œuvre Notre-Dame, Straßburg, 30 March -8 July 2012) ed. by Stefan Roller; Martin Büchsel, Die wachsame Müdigkeit des Alters. Realismus als rhetorisches Mittel im Spätmittelalter, in “Artibus et Historiae” , Vol. 23, No. 46 (2002), p. 21-35.

© 2013 – 2023 cesatiecesati.com | Please do not reproduce without our expressed written consent

Alessandro Cesati, Via San Giovanni sul Muro, 3 – 20121 Milano – P.IVA: IT06833070151